Cannabis advertising and patent medicine’s past

Our first paid advertisement launched this weekend the Cannabis Chronicles blog – many, many thanks to Mary Jane’s House of Glass for being our first official sponsor!

With that launch, I started to get curious about whether their ad is actually The Columbian’s first cannabis-related advertisement in history. So I went back into the archive to see what sort of patent medicine ads for cure-alls we might have had in the early 1900s.

Many patent medicines back in the 1800s and very early 1900s included cannabis as an active ingredient, along with opiates, heroin and a host of other things – which often weren’t listed on labeling because it wasn’t required until 1904 (and even after that it wasn’t always done).

Medicines like Rogers Excelsior Corn Cure (I assume they mean corns on your feet), for instance, had this ingredient list, according to an old book of formulas I found online:

ROGERS’S EXCELSIOR CORN CURE

Fluid ext. cannabis indica 1 dr.

Sulph. morphine 20 gr.

Salicylic acid iogr.

Collodion to make 2 fl. oz.

Mix well.

Pare the corn down thin, apply till a coat forms; do

so twice or more, and you can pick the corn out.

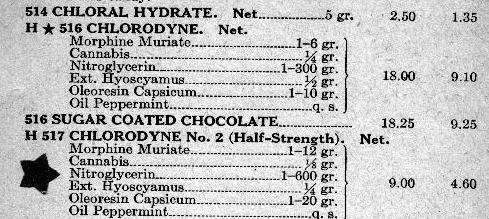

There’s also something called Chlorodyne that has a pretty crazy ingredient list (and was advertised for coughs, colds, asthma and bronchitis):

Neither of those products were advertised in The Columbian in 1902, a random year that I picked to look through. But there were other patent medicine ads on almost every page of The Columbian that year – which was a lot more than I thought I would find.

Here’s a list of some of them: Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery, Cascarets, Ely’s Cream Balm, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, St. Jacob’s Oil, Castoria, Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral, Carter’s Little Liver Pills and Dr. Miles’ Nervine.

Most were made up of an odd assortment of herbs. For instance:

Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery included blood root (herbal respiratory aid), Oregon grape root (herbal treatment for skin diseases), stone root (herbal congestion aid), Queen’s root (god knows what this was used for), sacred bark (herbal laxative) and cherry bark (an herbal remedy for colds).

Cascarets was made from the bitter tasting bark of a species of buckthorn tree that grows in this region. It was used as a laxative by Native Americans before the patent medicine folks got hold of it.

St. Jacob’s Oil was a bit more racy. Here’s its ingredient list:

ST. JACOB’S OIL

Gum camphor 1 oz. (antiseptic menthol herb)

Chloral hydrate 1 oz. (sedative, hypnotic drug)

Chloroform 1 oz. (a knock-out drug)

Sulph. ether 1 oz. (an anesthetic)

Tinct. opium y 2 oz. (euphoric narcotic drug)

Oil origanum ^2 oz. (oregano, the kitchen spice)

Oil sassafras , ^ oz. (root beer ingredient, flavor)

Alcohol Yz gal. (depressant, etc.)

Mix.

Surprisingly, none of the medicines I looked through for that year included cannabis as an ingredient – but it’s entirely possible that we did have some advertisements for patent medicines that included the plant either before or after 1902.

One of the things that interests me about this, though, is the herbal medicine component.

I think one of the aspects of cannabis and the recreational market is that the drug is returning, at least in some ways, to its origins as an herbal medicine. Cannabis, after all, has been used for thousands of years by a host of cultures for a wide range of illnesses (and of course as a recreational drug).

And now that it’s legal in Washington, some folks have gone back to using it as an herbal remedy for things like pain, insomnia and digestive problems.

And while we obviously don’t want to go back to the days of mysterious patent medicines with contents that could do more harm than good, in the modern age we can test, study and learn about a wide variety of herbal medicines that our ancestors used, like cannabis.

The recreational market, while it doesn’t let residents grow their own plants, does provide access to the plant for those that would want to use marijuana that way. And the lab testing and labeling of the product under I-502 lets users know at least something about the substance they’re about to ingest, which is more than they had back in the patent medicine days.

As it gets more out in the open, I think our understanding of potential uses (as well as things it shouldn’t be used for) of cannabis will become far more broad. And that’s safer for everybody.

Much safer than hiding in the closet or judging it without looking at the history or science.

Anyway, bit of a rambling post, but that’s my two cents for the day.

Cheers,

-SueVo (sue.vorenberg@columbian.com)

![Rogers1[1]](https://cannabis-chronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/Rogers11-174x400.jpg)